Christian Heritage

Site of the original home of Aengus Mac Nadfraich father of St Naul.

Slieveardaghs Christian Heritage – Psalter of Aengus Mac Nathfrach, King of Cashel

“Oxford the 9th of August 1673”

“This book is a famous copy of a great part of the Book of St. Mochuda of Cong, in which is contained many divine things, most of which documents the antiquities of the ancient houses of Ireland, a catalogue of their Kings, of the coming of the Romans into England, of the coming of the Saxons, and of their lives and regimes; a notable calendar of the Irish Saints of the Roman breviary until that time; a catalogue of the Popes of Rome; how the Irish and the English were converted to the Catholic faith; with many other things, as the reader may find, and so understanding what they contain let him remember. – Tully Conry”

Thus is recorded on a note pasted on the inside of the cover of a copy of the Psalter of Cashel written by Aengus Mac Nathfrach, King of Cashel, Copied in 1453 for Edmund Mac Richard Butler in Pottlerath by Seagan Buidhe O’Cleirigh. And now preserved in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

The Story of Slieveardagh and its Christian heritage begins with the Baptism of Aengus Mac Nathfrach at Cashel. A celebrated anecdote is told about this King Aengus. It is said that when St Patrick was conferring the Sacrament of Baptism upon him he accidentently laid the crosier on the Kings foot. The crosier pierced his foot, causing it to bleed profusely. So great, however, was the Kings devotion, that he did not make any sign of uneasiness, but patiently bore the pain, thinking it was part of the ceremony. ‘This crosier (the celebrated Irish relic known as the Bachal-Iosa, i.e., the Staff of Jesus) was preserved in Armagh until the English invasion (Cromwell) when it was brought to Dublin and kept at Christ Church Cathedral. But alas! At the time of the reformation it was publicly burned in the streets of the city’.

The first recorded missionary to Ireland was Palladius, who was probably from Gaul [France]. He was sent by the Pope to be bishop to the “Irish who believe in Christ”. Patrick himself stated that Palladius’ mission was a failure. However, other historical documents from outside Ireland indicate that the mission of Palladius was very successful, at least in Laigin (Leinster), and that he set up a number of churches. Tradition says that Palladius’ visit to Ireland was in the year 431.

In the Ossory Archaeological Society publications, papers attributed to Dr James Lanigan (1779 -1812) Bishop of Ossory deal with the Parish of Kilmanagh. According to Dr. Lannigan there are two patron Saints of Kilmanagh – Saint Edan or Enda whose feast is assigned to the 31st Dec and St. Natalis, or Naul, – Nailé ‘as Gaeilge’, whose feast day is set down in the Martyrology (recorded calender of events) of Tallagh as the 31st July. It is very probable that St Nathalis was the son of Aengus Mac Nathfrach, King of Cashel (killed 490).

Dr Lanigan says that little or nothing would be known about Nathalis were he not highly praised in the lives of St. Senan of Inniscathy (Scattery Island on the Shannon), who, when young, was a pupil of his, having been directed to his monastery by the Abbot Cassidus. This monastery was situated in Dún-Aengusa-Mac Nadfraich called after the first Christian King of Munster who resided in Cashel; was later known as Rath a’Photaire (Rath of the potter) later anglicized to Pottlerath a townland near the Munster River in Kilmanagh Parish, Co. Kilkenny.

In the metrical life of St Senan (translated) we read: –

“In a vision, an order is given

By the Lord of Heaven, to the abbot Cassidan

To send the novice to the illustrious Abbot Nathalis

To be fully instructed, under his rule and discipline,

Even at that time, Nathalis’ name was well known to fame

With him a large community dwelt in religious unity

A hundred and fifty brethren, learned and holy men”

This number must have increased very much, if there is any truth in the following story.

It is written that the monks of Dún-Aengusa-Mac Nadfraich paid a visit to their brethren at the monastery of Gort-frioch (This is the town land of Gortfree beside The Munster River in Ballingarry Parish, the river divides the modern Parishes of Ballingarry and Kilmanagh – Counties Tipperary and Kilkenny – as well as the provinces of Munster and Leinster. According to local folklore the site of this monastery is at the location of an old graveyard now dis-used.). When they arrived there the Abbot observed he had forgotten his breviary. Word was immediately sent back from one to the other by the monks, whose long line reached Pottlerath about two miles distant, and the breviary was forthcoming without delay.

St Naul flourished about the year 520, his death is assigned to the 27th January 564. From the following references, found in the annals of the Four Masters, Pottlerath must have been a place of importance and distinction in ancient times.

Under the year 780 we read: “The fifteenth year of Donnchadh Maeloctraigh, son of Conall, Abbot of Kilcullen and scribe of Cill-manach, died.” At the year 802 “Lemnatha Cill-manach died”. In the year 843 “Beasal, son of Caingne, Abbot Cill-manach died.

According to Dr. John O Donvan, the ancient name of Pottlerath was Dun-Aengusa-Mac Nadfraich –i.e., the fort of Aengus Mac Nadfraich, the first Christian King of Munster. It is worthy of note and very significant too, that Naul, the patron saint of Kilmanagh, was son of this same prince; and also that a holy well, known as Tobernedaun, or St Enda’s well, preserves the name of St Enda of Arran, whose sister, Sant, was wife of Aengus, and mother of St Naul. There are cures documented in the Ossory papers attributed to the waters of this well

I cannot find any specific reference to Killenaule in Dr Lannigans papers; however, Dr John O’Donovan (noted Gaelic Scholar Mid 1800’s) in his reference to St Naul describes him as the Abbott of Killenaule. (“Cill náile” – Cell or Church of Naul). Killenaule folklore may be able to identify the site of his ancient church.

St Sineach is given as the Patroness of Crohane. The Gaelic historian O’Hanlon says “she is mentioned on Oct 5th by the Feilire of Aengus, as the daughter of Fergna of Cruachan Muige Abnae in Eoghanacht Cashel”. Maurice Lenihan another Gaelic scholar says “the virgin is likely the sister of St Senachus, Bishop, who was with St Ruadháin (probably founder of Daoire na Bflann in the 6th century) and St Columba of Terryglass among the pupils and disciples of St Finian of Clon-errard who helped develop the early Church in Ireland, (Finian of Clonard, Saint, died in -549.)

Crohane must be identified with the Cruachan (Crohane) of St Sinech he says, and the denomination of Magh Abhna has been reformed into Mowney a neighbouring parish in the barony of Slieveardagh.

An ecclesiastical establishment had existed at an early period in Crohane. St Sineach lived in Crohane circa 450 – 550. It was a parish before 1200. The old church fell into disrepair around 1400. Her acts are not known to exist. Up to 1810 says O’Hanlon, her festival was remembered in Ballingarry on Oct 5th. (‘A pattern day was held in Ballingarry Oct 5th every year but in 1810 was stopped, as the celebrations bore little resemblance to celebrating the sanctity of St Sineach’), The holy well associated with the Saint was run dry, O’Donovan says, when he saw it (Sept 1840) but it will come to in winter again. O’Donovan also says Crohane was formerly Cruacháin in Eoghanacht Cashel.

In 1840 J.O’Donovan wrote that the foundations of the last Catholic Church were 28’ by 22’. About half a furlong South east of the graveyard were the ruins of a circular castle. It was 21’ – 6” in diameter and the walls were 9’ thick.The south and east walls were still there in 1840 and were 20’ high.

Church of Ireland Crohane. Built on the original site of the ancient church settlement. St Sineachs well has been pipe drained to a nearby stream, there is no sign of its original location.

O’Donovan also says Crohane was formerly Cruachan in the Eoghanacht. In the Feilire Aengus, Crohane is given as the round hill of Mowney . This parish is bounded on the west by the parish of Killenaule, on the east by the parish of Mowney, on the north and north east by the parishes of Lickfinn and Ballingarry. The parish is in Slieveardagh Barony, and an amount of its land would be at present in Ballingany parish, though the old church ruin is in Drangan.

This is the place called Cruachan Muighe Abhnae i.e. Croghane Mowney in the Festiology of Aengus, at Oct 5th for the glossographer places it in the territory of Eoghanacth Chaisil. This is rendered absolutely certain by the existence of the well of the Patron Saint and of other names of places in its vicinity, which the ancient authorities place in Eoghanacth Chaisil as Doire na bFlann etc. The name signifies the round hill in the plain of Abhna, which may be interpreted the plain of the river. Magh Abhnai, the name of the plain is still retained in that of the parish of Mowney which bounds Crohane on the east.

THE GREAT BATTLE OF CROHANE 852

It is not generally known that Crohane was the scene of a battle in which the Norwegians were defeated with terrible slaughter in the year 852. Up to this time the annals record the Lochlanns had not suffered so great a loss in all Eire. In an ancient compilation known as “Three Fragments of Annals” translated from the Irish by J. O’Donovan, the following account of the battle is given:

“The men of Munster sent messengers to Cearbhall (son of Dunlaing) to come. They also requested that he bring the Danes with him”. (The Danes were enemies of the Lochlanns at the time). They asked for help to assist and relieve them against the Northmen who were harassing and plundering them at that time. Clearbhall came with his army of Danes and Gaeidhils and when the Lochlanns saw them they were filled with fear. From a high place (Crohane Hill) Cearbhall addressed his own people first, and then the Danes. The speeches are recorded in the book. They then rose out and attacked the Lochlanns. The Locklanns fled to the woods which were then surrounded on every side by Cearball. They killed and slaughtered the Locklanns at Cruachain in the Eoghanacht (Crohane) this victory was gained in 842. There is a field in Crohane called “The Canauves or Hodgins Canauves” (Irish for Bones).

In “A history of Ser Kieran” published 1992, about Clareen Parish, Co. Offaly, it states that Cearbhall was buried in Ser Kieran’s churchyard in 885. There is a burial slab with a Celtic Cross marking his grave. The book states he was the most famous of the Kings of Ossory ( He ruled Ossory for 40 years according to the “Book of Leinster”). In 872 he became King of the Danes in Dublin and was recognised as such until his death 13 years later his descendants are also buried in Ser Kieran’s graveyard. (Bill Martin in conversation with the late Michael Hall, Kyle , Drangan, Co.Tipperary)

Note: A church in Ballykerin;

in 1620 a chapel of Ballykerin is mentioned as parcel of the parish of Crohane.

The old church of Crohane or Cruachan Magh Abhna was situated in the townland of Crohane Lower on the side of a valley, but all the walls are now destroyed down to the very foundations; it can be ascertained from them however that the church, or part of it, was 28’ in length, and 22’ in breadth. The walls were built of slaty stones cemented with lime and sand mortar. Its graveyard which is a large one, is still in use, but it contains no ancient monument. The Ord. Survey gives the site of the present Protestant church as on the site of the old one-likely its predecessor.

About 150 yards to the north of the graveyard there is a holy well called after the virgin, St Sinech, the patroness of Cruacha Magh Abhna, but no stations have been performed at it since 1810. It was run dry, O’Donovan says, when he saw it (Sept 1840) but it will come to in winter again. “Sinech daughter of Fergna of Croghane-Moy-Owney”, is a quotation from Aengus the Culdee.

In 1640, there were 4 acres of glebe land with the church. They were in Crohane, near the lands of Ballykirine, tithes were £25. There is in the parish a townland called Kilenahone given as the church of the cave in F.N Bk. Coolquill townland is given in Laffan as Coolkile.

“In Bishop Butler’s Visitations 1752 we find says O’Hanlon, that he visited Ballingarry chapel dedicated to the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin and found it in good repair. There were also two Parishes without chapels besides Ballingarry, one dedicated to St John the Baptist called the parish of Lismalin, the other, the parish of Crohane dedicated to St Sinech, feast day celebrated on Oct 5th. The lot were under the pastor ship of Rev Lawrence Lonergan”.

Parish of Lismolin

The old Catholic Church in Lismolin was dedicated to St. John the Baptist. In “Calender of Documents”, Survey Year 1302-07 on Taxation of Parishes, Lismolin is mentioned. In “Visitations of Archbishop O Hedian” Lismolin is mentioned as a Parish in 1437. Some time after it became the property of the Cistercians of Hoare Abbey, Cashel. Tradition states that Cromwell destroyed the church in Lismolin. Canon O’Rourke wrote that on 11th July 1704 Fr Wm. Kelly (72 years old) was the registered PP of Ballingarry, Crohane and Lismolin. He livid in Gragaugh and is buried in Lismolin. Fr Kelly was the victim of special persecution at the hands of Baron Butler of Lismolin. He often sought refuge with his sister, Mrs Croke at Ballingarry. When Fr Kelly died, six Croke boys carried his coffin to Lismolin graveyard at night time.The location of his grave is unknown. At present the graveyard is still in use and the vestry walls and gable wall of the Protestant Church are still standing. Inside are two stone slabs to the memory of Scott brothers from Scotsborough. The church was built around 1716 on the site of the Catholic Church.

Parish of Mowney:

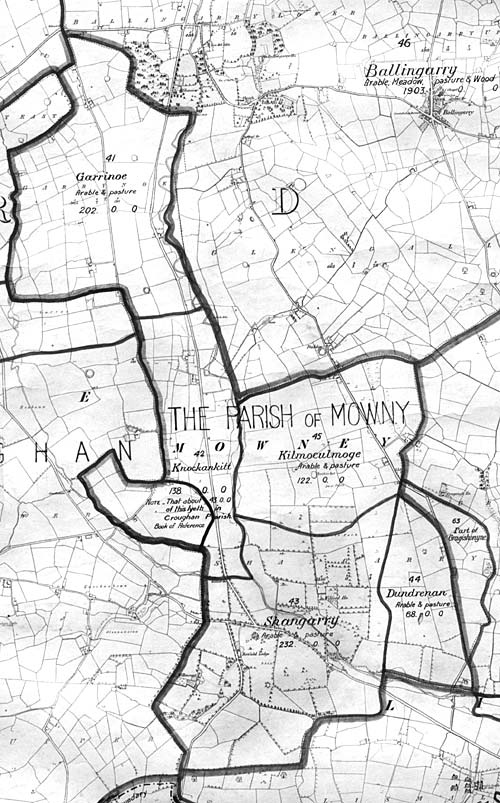

Mowney Parish is mentioned in the Papal Taxation lists of 1294 and 1302 and in the visitation list of churches made by Archbishop Richard O’ Hedian in 1432. Entry to the location is by a short disused boreen near Meaghers, (Gragaugh). An identifiable passage running west by a whitethorn hedge from the gate would seem to have been the road to the church site. The area is drained by the Kings River, the old name being the River Guineagh – In dry hot summers the outline of six or more circular foundations, approx. 8 – 10ft Dia. can be seen on the higher ground overlooking the site of the church, The church is recorded on the Ordinance Survey sheet for the area.

_______________________________________________________.

The Settlement and Architecture of Later Medieval, Slieveardagh, County Tipperary. – Richard Clutterbuck Volume II

This thesis is presented in fulfilment of the regulations for the degree of M.Utt in Archaeology, University College Dublin., Head of Department: Supervisors: Prof. Barry Raftery, Dr. Tadhg O’Keeffe, Dr. Muiris 0’Sullivan, August 1998

Shangarry Church site, Shangarry Td., Mowney Pro, 55110, S 304461, T1055-047, 311997

Location: Shangarry is situated in the south of the barony on the side of the Kings River valley in the hills in a section of Shangarry townland called Knockroe (Fig. 26; 32). The church site is 2.5km south of Ballingarry (4) and 2.5km north by north-west of Lismalin (42). Shangarry church site is at an altitude of 140 metres in a field sloping to the west. The church site is exposed with a westerly aspect overlooking the Kings River valley.

History Mowney was also known as Mog-Owney (OS Letters Co. Tipp I, 196) and may have been the location of the church called Magoury in the Ecclesiastical Taxation 1305-07 (Cal. Doc. Ire. 1302-07,285). Shangarry church is marked as a church site in the Ordnance Survey maps.

Description and comment Shangarry church site consists of a circular enclosure with external and internal ditches. This appears to be a pre Norman church site though no evidence remains for a building or church.

The evolution of the Celtic Church

St. Patrick left behind him a band of well-educated, devoted men, who greatly venerated their master and sought to follow in his footsteps. Ireland was unique in being the only western European country to which Christianity came without Roman conquest. The fall of the Roman Empire in the west, the expiration of Latin institutions in Britain, and the barbarian conquest in France and Italy isolated Ireland even more.

The native Celtic Church and civilization flourished. Later Celtic Christians brought the gospel to the “barbarians” in Belgium, Holland, France, Switzerland, Germany, Italy etc. who had replaced the order of the Roman Empire.

She differed in many ways from the Churches in the west: in doctrine, in church government, in the time of celebrating Easter, celibacy, and the form of the tonsure. There were no Archbishops, and bishops were almost as numerous as parishes, the sees often descended from father to son. The clergy were subject to taxation, to secular jurisdiction, to military service; there were no tithes, the clergy were supported by voluntary gifts; the Scriptures were much studied. She rejected all foreign control – including control from the pope -, and acknowledged Christ only as Head of the Church. She was primarily a monastic Church, without the centralized, geographically ordered network that the Roman Church had inherited from the Roman Empire.

The fame of Ireland for its monasteries, missionary schools, and as the seat of pure Scriptural teaching, rose so high, that it received the name “The Isle of Saints and Scholars.” Roman missionaries had arrived in southern England and there were disagreements between the Celtic church and the Roman church. This was resolved at the Synod of Whitby of 664 in which it was decided that the church in Britain would follow the Roman practices. However, the people in Ireland resisted the changes and so Romanism did not have much impact in Ireland.

One of the most important works of the Irish monasteries, besides catering for the needs of the local population, was in the production of books. These are the great illuminated manuscripts, such as the Book of Kells, which were hand written copies of the Bible and other books. Beautifully decorated by hand, these books were usually written in Latin. After the synod of Whitby in 664 many Anglo-Saxon nobles and clergy went to Ireland, where they started to live in monasteries or just went to receive a good education. The mother tongue of the native people was, by comparison with other European languages, so complex that to those who had already mastered Old Gaelic the learning of Latin was relatively easy. Learn Latin they did, perhaps as early as the fourth century through contacts with traders from the Roman Empire, but certainly by the fifth century, with remarkable consequences. The Irish were the first people to adapt the Roman alphabet and the composition of a grammar for the writing of Latin in Old Irish. This happened 500 years before the writing of the alphabet and grammar for Latin in Old English at the end of the 10th century.

The labors of the Irish were not confined to their own country. Naturally fond of traveling, and being energized by a love for their vocation, many missionaries left Ireland under the leadership of a loved and devoted abbot. Western Europe truly owes a debt to these Irish pioneers of Christianity in the Dark Ages! – Gortfree, Pottlerath, Crohane, Derrynaflan and Daoire Bhoile would have contributed greatly to the supply of learned and pious people within Ireland and probably on the continent of Europe too.

(Read, “How the Irish saved civilization” by Thomas Cahill)

Parish Survey

The survey of 1302 – 7 (survey type unknown, probably ecclesiastical) Identifies the parishes in “Slefardach” (Slieveardagh) before 1200 as:-

- Derenflan (Derrynaflan) – Killenaule

- Scornan (Graystown) – Killenaule

- Lismol (Lismolin) – Ballingarry

- Baligraffny (Killboy near Laffansbridge) – Killenaule

- Church of the vill of Goddard (Lickfinn) – Ballingarry

- Moyrachne (Mowney) _ Ballingarry

- Kilbrenyn (Kilbrennal) – Killenaule

- Kildenale (Killenaule) – Killenaule

- Rectory of Boulegh (Boulic) – Gortnahoe/Glengoole

10.De Garda ( Gare alias Ballingarry) – Ballingarry

Bill Martin 13/12/2012