Mullinahone.

Mullinahone from the air.

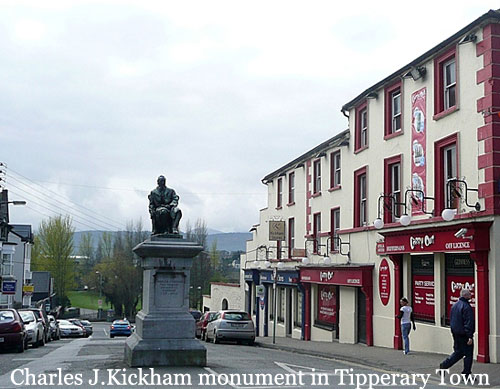

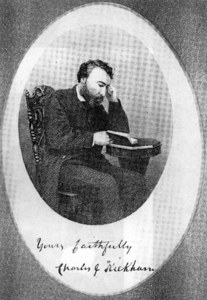

Charles J. Kickham (1828–1882)

Author and Fenian leader. Charles J. Kickham was born on 9 May 1828, at Mullinahone in Co. Tipperary. A cousin of John O’Mahony, and David Power Conyngham Kickham was the eldest of eight children of a prosperous shopkeeper. He was educated at Mullinahone, Co. Tipperary. It was hoped that he would practise medicine but an accident with gunpowder at the age of 13 permanently damaged his sight and hearing. His father was involved in anti-tithe meetings during the 1830s. The first popular movement to attract his attention was the temperance crusade launched by Fr Theobald Mathew in 1838. Kickham was influenced by the romantic ideological nationalism of Thomas Davis and the Young Irelanders. He was a also a supporter of the Repeal Association. He wrote pieces in the Nation, the Celt, the Shamrock and theIrishman. He founded a branch of the Young Ireland Confederate Club in Mullinahone in 1848 and was forced into hiding after the unsuccessful rising at Ballingarry, Co. Tipperary.

In 1850 he worked for Tenant Right League but lost faith in political agitation after its failure in 1855. Kickham’s politics became more radical and he joined the secret nationalist organisation, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) or the Fenians, in 1860. He was a committed separatist. He had a deep sense of veneration for America as a model of independent democratic nationhood. He travelled there as an IRB delegate. He rose quickly in the ranks of this movement and was appointed by the Fenian leader, James Stephens, to sit on the Supreme Executive with Thomas Clarke Luby and John O’Leary. He contributed political articles to James Stephens’s nationalist paper and IRB organ, the Irish People, which he later edited. This gave him the opportunity to develop his talents as a controversialist and propagandist. He dealt with many topics in its pages but his treatment of clerical attacks on Fenianism earned him lasting fame.

He was on the editorial staff of the Irish People and later became joint editor. On 15 September 1865 the Dublin Police, directed by the Castle, took possession of the Irish Peopleheadquarters at 12 Parliament Street and seized the entire contents of the office. The few members of the staff still on the premises were arrested and others were picked up on the street or in their homes.

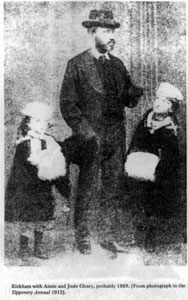

Irish People documents revealed Kickham’s role in the Fenian conspiracy. On 11 November 1865 he was arrested with James Stephens. Nearly blind and almost completely deaf, Kickham was charged for writing ‘treasonous’ articles and for committing high treason. He was tried before Judge William Keogh and sentenced to fourteen years penal servitude. He was sent to Mountjoy prison. On 10 February 1865 he was transferred to Pentonville Prison near London. During this time his health deteriorated because of poor prison diet. On 14 May 1866 he was transferred to Portland Prison and later to the invalid prison at Woking in Surrey, where he spent the remainder of his term. He was released in 1869 with his health severely impaired and returned to Mullinahone, Co. Tipperary. Kickham was now the leading Fenian at liberty in Ireland. Following the annulment of the return of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa as MP for Tipperary, Kickham stood and polled 1,664 votes—defeated by just four votes.

Irish People documents revealed Kickham’s role in the Fenian conspiracy. On 11 November 1865 he was arrested with James Stephens. Nearly blind and almost completely deaf, Kickham was charged for writing ‘treasonous’ articles and for committing high treason. He was tried before Judge William Keogh and sentenced to fourteen years penal servitude. He was sent to Mountjoy prison. On 10 February 1865 he was transferred to Pentonville Prison near London. During this time his health deteriorated because of poor prison diet. On 14 May 1866 he was transferred to Portland Prison and later to the invalid prison at Woking in Surrey, where he spent the remainder of his term. He was released in 1869 with his health severely impaired and returned to Mullinahone, Co. Tipperary. Kickham was now the leading Fenian at liberty in Ireland. Following the annulment of the return of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa as MP for Tipperary, Kickham stood and polled 1,664 votes—defeated by just four votes.

In spite of his ill-health he moved to Dublin and resumed his career in the IRB. He became member of the Supreme Council in 1872 and was its first chairman until his death. He believed that the IRB must concentrate only on winning complete independence for Ireland. If it became involved with any other issue (such as land reform),  it would become corrupt and lose sight of its real objective.

it would become corrupt and lose sight of its real objective.

For Kickham, an Irish Republic could be won only by a rebellion led by the IRB and the time to rebel was when Britain was involved in a major war: ‘England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity’. Unfortunately for Kickham there was no major war in the 1870s. He opposed with limited success the involvement of Fenians in the Home Rule Movement, in the New Departure, and in the Land War. He did not condone the agrarian outrages. He regarded the Land League’s ‘No Rent Manifesto’ as ‘criminal and cowardly’. In his opinion the Land League ‘was bringing communism upon the country’. He was absolutely convinced that parliamentary politics was a ‘harmful waste of time’.

Kickham was a prominent ballad writer and the author of several books. His first

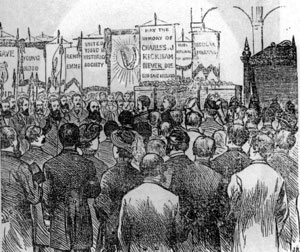

novel Sally Cavanagh was written while he was in Woking prison. His sentimental, deeply nostalgic and farcical Knocknagow; or The Homes of Tipperary (1879) was a huge and instant success and made him one of the most popular novelists of the nineteenth century. He published a volume of collected poems and stories in 1870. He is also well remembered for his songs, ‘Rory of the Hill’, ‘The Irish Peasant Girl’, and the ballad ‘Patrick Sheehan’. Kickham was very badly off on many occasions and a national collection to help him was made in 1878. In his later years he did much of his writing from his bed. In 1880 he was knocked down and run over by a jaunting car in College Green and had a broken leg. On 19 August 1882 he had a stroke and died on 22 August 1882 at the age of 54, at Blackrock, Co. Dublin. His funeral was followed to Kingsbridge Station (now Heuston Station) by nearly ten thousand mourners. In contrast, he was buried in Mullinahone without any local clergy. The funeral oration was given by John Daly, the Limerick Fenian.

novel Sally Cavanagh was written while he was in Woking prison. His sentimental, deeply nostalgic and farcical Knocknagow; or The Homes of Tipperary (1879) was a huge and instant success and made him one of the most popular novelists of the nineteenth century. He published a volume of collected poems and stories in 1870. He is also well remembered for his songs, ‘Rory of the Hill’, ‘The Irish Peasant Girl’, and the ballad ‘Patrick Sheehan’. Kickham was very badly off on many occasions and a national collection to help him was made in 1878. In his later years he did much of his writing from his bed. In 1880 he was knocked down and run over by a jaunting car in College Green and had a broken leg. On 19 August 1882 he had a stroke and died on 22 August 1882 at the age of 54, at Blackrock, Co. Dublin. His funeral was followed to Kingsbridge Station (now Heuston Station) by nearly ten thousand mourners. In contrast, he was buried in Mullinahone without any local clergy. The funeral oration was given by John Daly, the Limerick Fenian.

Writings, Biography,& Studies. James Maher (ed), The valley near Slievenamon: a Kickham anthology(Kilkenny 1942). James Maher (ed), Sing a song of Kickham: songs of Charles J. Kickham (Dublin 1965). Richard J. Kelly, Charles Joseph Kickham: patriot and poet (Dublin 1914). James J. Healy, Life and times of Charles J. Kickham (Dublin 1915). William Murphy,Charles J. Kickham: patriot, novelist and poet, intro by Thomas Wall (Blackrock 1976). R. V. Comerford,Charles J. Kickham: a study in Irish nationalism and literature (Portmarnock 1979).

“The Valley of Slievenamon” with Maureen Hegarty.

‘Slievenamon’ lies on the plain of ‘Femen’ [Irish, femininity], and the magical ‘Sídh ar Femen’ is near its peak. According to oral tradition, Sliabh na mBan is named for the women who raced each other up the slopes for the privilege of lying with the legendary warrior Fionn mac Cumhaill in ancient times. Other Fenian stories recount that Fionn got his mystical thumb wisdom, on Slievenamon, when he catches it in the door-jamb of a cairn to the ‘Otherworld’ (This version of how Fionn gained his knowledge dates from the 8th century, the more well-known version, is the tale of the Salmon of Wisdom). It is also at Sliabh na mBan that Fionn chooses Gráinne for his own, and where The Fianna hunted boar. Earlier ‘Bodb Derg’ was thought to keep supernatural pigs here that reappeared alive after they had been eaten”.

‘Slievenamon’ lies on the plain of ‘Femen’ [Irish, femininity], and the magical ‘Sídh ar Femen’ is near its peak. According to oral tradition, Sliabh na mBan is named for the women who raced each other up the slopes for the privilege of lying with the legendary warrior Fionn mac Cumhaill in ancient times. Other Fenian stories recount that Fionn got his mystical thumb wisdom, on Slievenamon, when he catches it in the door-jamb of a cairn to the ‘Otherworld’ (This version of how Fionn gained his knowledge dates from the 8th century, the more well-known version, is the tale of the Salmon of Wisdom). It is also at Sliabh na mBan that Fionn chooses Gráinne for his own, and where The Fianna hunted boar. Earlier ‘Bodb Derg’ was thought to keep supernatural pigs here that reappeared alive after they had been eaten”.

Mullinahone a short history

In ancient Gaelic, this whole area, then heavily wooded, was called An Cuimseanach, suggesting an enclosed valley, and came to be known in medieval times as Compsey.

The Pass of Compsey, one of the two routes from Tara and Ossory in Leinster to Cashel in Munster, crossed the river (a tributary of the River Anner) at the ford of Aghmonenahone at Mullinahone, under the old Norman keep in modern Carrick St., then continued via Cappaghnagrane to Fethard and Cashel.

The Norman St Aubyn / Tobin family, feudal Lords of Compsey, were enjoined by Royal Decree to cut down the local forest to “ensure safe passage for travellers“.

According to local folk memory, an army led by Edward Bruce, Earl of Carrick (in Scotland) and his brother, the Scottish King Robert the Bruce, spent a week in 1317 travelling the short distance from Callan to Cashel, looting and pillaging on all sides.

Cromwellian troops visited in 1654 to dispossess the Tobins of their estates; most of the family was transplanted to Connacht.

In 1691 a detachment of King William III‘s army camped nearby was detailed to ‘burn the Compsey’ as it was believed to harbour rapperees; however, the order was never carried out.

During the 1798 Rebellion, local insurgents were defeated on Carrigmaclea / Carrigmoclear Hill.

The Great Famine and its immediate aftermath reduced the population of the area by as much as 27% over a decade of starvation and emigration. Mullinahone also suffered considerably during the late C19th Land War.

The parish and people were very much involved in the War of Independence; a monument in the village square commemorates locals who lost their lives.

Killaghy Castle

Killaghy Castle, founded in 1206, was the seat of the St Aubin / Tobin barons of Compsey. Originally constructed as a motte and bailey, it was walled and fortified over the next century, and a Tower House was built c.1500, with a long house added shortly afterwards.

Killaghy Castle, founded in 1206, was the seat of the St Aubin / Tobin barons of Compsey. Originally constructed as a motte and bailey, it was walled and fortified over the next century, and a Tower House was built c.1500, with a long house added shortly afterwards.

The manor was granted by the Cromwellian administration to a Colonel Green, whose granddaughter married William Despard in 1708. Their descendants remained in residence for over 150 years.

The C18th saw the construction of two further buildings forming the structure of Killaghy Castle as it stands today, including the estate walls adjoining the modern village.

The castle has undergone extensive restoration, and is now available for rent as self-catering accommodation at 2500 – 3900 Euro Per Week, depending on the number of people, with a recommended maximum of 16.

A series of plaques guide visitor through the village and surrounding areas, from the old courthouse to a famine soup kitchen and the ruins of an ancient monastery. The history of the area has been well documented in a recent book by Michael Larkin.