Famine Warhouse

An Etching in plaster of the original Widow McCormack’s family home from a pencil drawing published in the Illustrated London News dated August 12th 1848.

An Etching in plaster of the original Widow McCormack’s family home from a pencil drawing published in the Illustrated London News dated August 12th 1848.

Father John Kenyon’s involvement in the preparation for war caused serious concerns for his Bishop Dr Kennedy. When in April 1848, he encouraged a crowd of ten thousand people at Templederry to arm themselves; Dr Kennedy immediately suspended him from clerical duties. He was presented with an ultimatum to either give up politics or be expelled from the priesthood. A compromise was arrived at whereby he agreed that he would not involve himself in the rising unless he considered that there was a reasonable chance of success. Unfortunately he did not explain this constraint to his colleagues – a fact that caused much misunderstanding and anger as the Confederates assembled in Ballingarry County Tipperary a few weeks later.

On Thursday 27 July as the Confederates assembled at Ballingarry, William Smith O’Brien dispatched Thomas Francis Meagher, to request Father Kenyon to lead out his men. It was intended that Kenyon’s leadership would extend the rising to North Tipperary, and into Limerick where Richard O’Gorman was awaiting orders. Kenyon’s response was unexpected. He refused, stating that he was not prepared to become involved in “a bootless struggle.” Later he wrote in the parish register: “This evening I have heard of a rebellion in South Tipperary under the leadership of William Smith O’Brien – may God speed it.

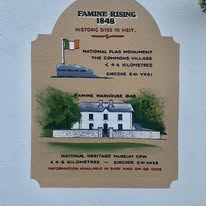

A Visitors’ Guide to the Famine Warhouse 1848

by Dr Thomas McGrath

During the Great Famine, 1845-1850, the Warhouse at Ballingarry, Co. Tipperary, was the scene of the principal action of the 1848 Rebellion by the Young Irelanders.

Young Ireland

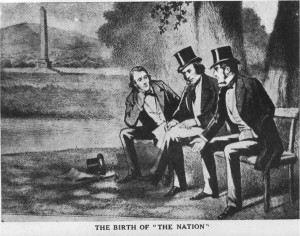

The Young Ireland movement which attracted journalists, barristers, historians and poets was initiated by the Protestant intellectual, Thomas Davis and comprised some of the most brilliant names in modern Irish history. Together with Charles Gavan Duffy and John Blake Dillon, Davis founded The Nation newspaper in 1842 to promote national self-determination, cultural identity and a pluralist Ireland.

The Young Ireland movement which attracted journalists, barristers, historians and poets was initiated by the Protestant intellectual, Thomas Davis and comprised some of the most brilliant names in modern Irish history. Together with Charles Gavan Duffy and John Blake Dillon, Davis founded The Nation newspaper in 1842 to promote national self-determination, cultural identity and a pluralist Ireland.

Thomas Davis (right)

The Young Irelanders were influenced by the interdenominational ideals of Wolfe Tone and the United Irishmen of the 1790s. They were a ginger group within the Repeal of the Union movement established by Daniel O’Connell to seek an Irish parliament. However, they differed from O’Connell in demanding an Irish parliament regardless of which British political party was in power and they did not rule out the use of physical force in all circumstances. The leader of the Young Irelanders in 1848 was William Smith O’Brien, Member of Parliament for Co. Limerick. O’Brien was an Irish Protestant aristocrat, son of Sir Edward O’Brien of Dromoland Castle, Co. Clare and descended from the High King of Ireland, Brian Boru, who defeated the Danes [Vikings] at the battle of Clontarf in 1014.

The Nation was an Irish Nationlist weekly newspaper, published in the 19th century. The Nation was printed first at 12 Trinity Street, Dublin from 15 October 1842 until 6 January 1844. The paper was afterwards published at 4 D’Olier Street from 13 July 1844, to 28 July 1848, when the issue for the following day was seized and the paper suppressed. It was published again in Middle Abbey Street on its revival in September 1849. –

The founders of The Nation Newspaper were three young men – two Catholics and one Protestant – who, according to the historian of the newspaper T. F. O’Sullivan, were all “free from the slightest taint of bigotry, and were anxious to unite all creeds and classes for the country’s welfare.”. They were Charles Gavin Duffy its first editor; Thomas Davis and John Blake Dillon.

Famine and Emigration

The Young Irelanders became increasingly discontented and radicalised by the horrors of the Great Famine, 1845-1850. The government was committed to the principle of free trade and its response had not been adequate to prevent deaths on a massive scale. As the famine progressed, the Young Irelanders denounced the government for not doing enough. O’Brien was the most trenchant critic of the government in the House of Commons. Of a total Irish population of eight million, a million people died during the Famine and another million fled into exile, mainly to North America.

1848: Revolutions in Europe

1848 was a year of revolutions throughout continental Europe. In February 1848, the King of

France was overthrown and a Republic proclaimed in Paris. The French Revolution sent political shock waves across Europe. Revolutions broke out in Berlin, Vienna, Rome, Prague, Budapest and Cracow and, at least temporarily, absolutist governments were replaced by liberal administrations, near universal suffrage was introduced and elections were held to constituent assemblies to draw up new national constitutions. It was described as the “springtime of the peoples”.

France was overthrown and a Republic proclaimed in Paris. The French Revolution sent political shock waves across Europe. Revolutions broke out in Berlin, Vienna, Rome, Prague, Budapest and Cracow and, at least temporarily, absolutist governments were replaced by liberal administrations, near universal suffrage was introduced and elections were held to constituent assemblies to draw up new national constitutions. It was described as the “springtime of the peoples”.

The Young Irelanders were deeply influenced by these events and the success of liberal, romantic nationalism on the European mainland inspired the movement to contemplate revolution in Ireland. O’Brien and Thomas Francis Meagher led a delegation to Paris to congratulate the new French Republic. Meagher returned to Ireland with the tricolour flag (now the national flag) – a symbol of reconciliation between the Orange and Green.

The fact that the continental revolutions were relatively bloodless led O’Brien to believe that he could attain a similar result in Ireland by manifesting the moral will and the moral force of a united people. He hoped to unite landlord and tenant in Ireland in protest against British rule. The Young Irelanders prepared for a Rising in autumn 1848. The government, however, forced their hand on 22 July 1848 by announcing the suspension of Habeas Corpus which meant that the Young Irelanders could be imprisoned on proclamation without trial. O’Brien decided that rather than let the government arrest the leaders of Young Ireland a stand had to be made.

A contemporary view of the battle at the Warhouse July 29th 1848

Rebellion

From 23-29th July 1848, O’Brien, Meagher and Dillon raised the standard of revolt as they travelled from Co. Wexford, through Co. Kilkenny and into Co. Tipperary. The last great gathering of Young Ireland leaders took place in the village of The Commons on 28 July. On 29 July, O’Brien was in The Commons where barricades had been erected to prevent his arrest. His local supporters – miners, tradesmen and small tenant farmers – awaited the arrival of the military and police. As the police from Callan approached the cross roads before The Commons from Ballingarry they saw barricades in front of them and, thinking discretion the better part of valour, they veered right up the road towards Co. Kilkenny. The rebels followed them across the fields. Sub-Inspector Trant and his forty-six policemen took refuge in a large two-storey farmhouse taking hostage the five young children who were in the house. They barricaded themselves in, pointing their guns from the windows. The house was surrounded by the rebels and a stand-off ensued. Mrs Margaret McCormack, the owner of the house and mother of the children, demanded to be let into her house but the police refused and would not release the children. Mrs McCormack found O’Brien reconnoitring the house from the out-buildings, and asked him what was to become of her children and her house.

O’Brien and Mrs McCormack went up to the parlour window of the house to speak to the police. Through the window O’Brien stated : “We are all Irishmen – give up your guns and you are free to go”. O’Brien shook hands with some of the police through the window. The initial report to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland stated that a constable fired the first shot at O’Brien who was attempting to negotiate. General firing then ensued between the police and the rebels. O’Brien had to be dragged out of the line of fire by James Stephens and Terence Bellew MacManus, both of whom were wounded.

|

||||||

|

||||||

| James Stephens |

Terence Bellew MacManus |

|||||

The rebels were incensed that they had been fired upon without provocation and the shooting went on for a number of hours. During the initial exchange of fire the rebels at the front of the house – men, woman and children – crouched beneath the wall. So great was the pressure of the crowd that one man, Thomas Walsh, was forced to cross from one side of the front gate to the other. As he crossed between the gate piers he was shot dead by the police. During lulls in the shooting the rebels retreated out of the range of fire. Another man, Patrick McBride, who had been standing at the gable-end of the house when the firing began – and was quite safe where he was – found that his companions had retreated. Jumping up on the wall to run to join them, he was fatally wounded by the police.

It was now evident that the position of the police was almost impregnable and a Catholic clergyman of the parish, Rev. Philip Fitzgerald, endeavoured to mediate in the interests of peace. When a party of the Cashel police under Sub Inspector Cox were seen arriving over Boulea hill an attempt was made to stop them by the rebels whose ammunition was low but the police continued to advance, firing up the road and it became clear that the police in the house were about to be reinforced and rescued. The rebels then faded away effectively terminating both the era of Young Ireland and Repeal but the consequences of their actions would follow them for many years. The McCormack family emigrated to the USA about 1853. Since that time the McCormack house (which was owned by a number of other families after 1848) has always been known locally as the Warhouse. In 2004 the State decided on ‘Famine Warhouse 1848’ as the official name of the house.

Trial, Tranportation, Exile

After the failure of the Rising, O’Brien, Thomas Francis Meagher, Terence Bellew MacManus and Patrick O’Donohue were captured and tried for high treason. Juries found them guilty but recommended mercy. Nevertheless they were sentenced to death by hanging, drawing and quartering. They refused to appeal. The sentences were, however, commuted by a special act of parliament to penal imprisonment for life in Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania) in Australia. There, they were joined by Young Ireland colleagues – John Martin, Kevin Izod O’Doherty and John Mitchel. Mitchel had been convicted of treason-felony and sentenced to fourteen years transportation in May 1848. Twenty-one locals from Ballingarry and the surrounding parishes were also arrested and jailed in Ireland.

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

Patrick O’Donohue |

John Mitchel

|

||||||

Other Young Irelanders escaped to France and the USA. John Blake Dillon returned from America and died as Member of Parliament for County Tipperary in 1866. James Stephens, John O’Mahony and Michael Doheny co-founded the Irish Republican Brotherhood (I.R.B) or Fenian movement in 1858. The IRB later organised the unsuccessful Rising of 1867 and the 1916 Rising which led to Irish independence.

Of those transported to Australia, a number escaped to America where they became leaders of the Irish diaspora. Meagher became a Union General leading the Irish Brigade in several great and bloody battles of the American Civil War. John Kavanagh who led the pikemen at the Warhouse died as a Captain serving under Meagher in the battle of Antietam. Meagher died as acting Governor of Montana. On the other hand, John Mitchel supported the south in the same war. He was later elected Member of Parliament for Co. Tipperary in 1875, the year of his death. MacManus died in San Francisco in 1861 and was accorded a famous funeral in Ireland.

Kevin Izod O’Doherty on his release served as a member of the Queensland legislature in Australia and later as an Irish M.P. Charles Gavan Duffy whom the government failed to convict at trial, re-opened the Nation which had been suppressed during the Rebellion, and became an M.P. He emigrated to Australia where he became Premier of the State of Victoria in 1871. Duffy later became the historian of the Young Ireland movement. John Martin following his release became a Home Rule M.P.

O’Brien was incarcerated on Maria Island, off the coast of Tasmania, and then in a two-roomed cottage (now the O’Brien Museum) within the Port Arthur penal colony. He received a conditional pardon in 1854 which was made unconditional in 1856 and allowed him to return to Ireland. He refused many offers from Irish constituencies to return to the House of Commons. He died in 1864 and is buried in the O’Brien mausoleum, Rathronan, Co. Limerick. His statue stands on O’Connell Street, Dublin.

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

Colonel John O’Mahony |

Michael Doheny |

|||||

Tipperary Honours the Men of 1848 (1948)

Sunday, the 29th July 1948, was a memorable day in Ballingarry, when people from various parts of County Tipperary, together with Government Ministers, Dáil Deputies, Senators, Army and F.C.A. Detachments, assembled to honour the memory of the men who raised the standard of revolt in the area 100 years before.

.

Long lines of soldiers of the regular army and F.C.A., accompanied by The James Stephen’s Pipe Band, Kilkenny and The Carrick Brass and Reed Band, marched from The Commons to “The Warhouse”. En route the salute was taken by Mr. James M. Dillon, Minister for Agriculture, and at The Warhouse addresses were delivered.

.

On the wall of The Warhouse a plaque, which bears the words “Remember 48” was unveiled.

.

A Guard of Honour was formed for the Ministers by members of Thurles Battn. F.C.A. under 2nd Lieut. J. Lambe. Lieutenants T. Butler, Ballingarry and P/ Moloughney, Dualla carried the colours in the parade. On the saluting base, with Mr. Dillon, were Very. Rev. Canon Fitzgerald P.P. Ballingarry, Gen. Richard Mulcahy, Minister for Education, Mr. Dan Breen T.D., Mr. M.J. Davern T.D., Mrs B. Ryan T.D., W. Quirke, Denis Burke and Frank Loughman; Professor D. Gwynn and Lt. Col. T. Halpin, representing the O/C of the Southern Command and Comdt. M. Hough Staff Officer F.C.A. Southern Command.

.

The parade, composed of one company of the 13th Infantry Battn. Clonmel and three companies of the F.C.A. was under the command of Comdt. W. Bergin. Capt. P.J. Lambe, Thurles, was in charge of F.C.A. units.

.

In his address rev. Canon Fitzgerald said that they were assembled that day in the company of members of their own Parliament, the members of their councils under the aegis of their own national Army, their own F.C.A. and their own Gardaí, due in no small way to the sacrifices of the men and women of 1848.

.

Professor Gwynn, grandson of William Smith O’ Brien, said that there could be no more fitting place than Ballingarry for them to pay tribute to the men who formed and led the Young Ireland Movement 100 years ago.

.

1948 Centenary Celebrations Committee:

| Chairman: | Very Rev. William Canon Fitzgerald P.P. V.F. |

| Vice-Chairman: | Dr. M. Breen |

| Treasurer: | Very Rev. William Noonan C.C. |

| Secretaries: | Thomas Luttrell N.T. & Richard Dunne |

.

Committee: Thomas Molloy P.C., Timothy Dunne P.C., Michael Kealy, Michael Maher, Hugh Cormack, Nicholas Dunne, Denis O’ Sullivan, James Egan, Martin Morrissey, John Aylward, Louis Fitzgerald, Oliver Fitzgerald, Godfrey Greene, James Power, Edmond Barrett & John Morris (Poynstown, Glengoole).

.

On the platform at 1948 commemoration at The Warhouse.

On the platform at 1948 commemoration at The Warhouse.

Group included: Gen. Mulcahy TD Minister for Education, Prof. Gynn, James Dillon TD Minister for Agriculture, Lt. Col. T. Halpin, Canon W. Fitzgerald P.P., Michael Davern TD, Fr. W. Noonan C.C. (On right at ground level, John Aylward)

.Mr. J. Dillon TD asked the assembled crowd how many of them knew where the Tricolour was first flown. Yes, at “The Warhouse” in 1848.

.

“The Minister said that looking back a hundrcd years ago to the day his grandfather John Blake Dillon was in Ballingarry, to 1803 when he won Tipperary from the Tories, to 1870 when his father John Dillon and his uncle brought Mitchel back to Tipperary and won the seat for nationalism again; to 1879 when Parnell sent his father to fight the cause in Tipperary he felt that though he was not born in Tipperary he had a claim to be there that day and the right to speak there. Canon Fitzgerald had referred to the fact that to-day we are a sovereign nation with our own army, our own Gardai and our own flag. He (speaker) would like to ask’ how many there present knew where that flag was first seen in this country; how many knew where that flag was first un-furled in ‘Anger’? It was on the ground on which they stood that day that it was unfurled 100 years ago, it was unfurled to Inspire not a party, not a faction, but a nation.

“The Minister said that looking back a hundrcd years ago to the day his grandfather John Blake Dillon was in Ballingarry, to 1803 when he won Tipperary from the Tories, to 1870 when his father John Dillon and his uncle brought Mitchel back to Tipperary and won the seat for nationalism again; to 1879 when Parnell sent his father to fight the cause in Tipperary he felt that though he was not born in Tipperary he had a claim to be there that day and the right to speak there. Canon Fitzgerald had referred to the fact that to-day we are a sovereign nation with our own army, our own Gardai and our own flag. He (speaker) would like to ask’ how many there present knew where that flag was first seen in this country; how many knew where that flag was first un-furled in ‘Anger’? It was on the ground on which they stood that day that it was unfurled 100 years ago, it was unfurled to Inspire not a party, not a faction, but a nation.

Never Despair

Poem written by William Smith O’ Brien in Clonmel Goal on the day he was sentenced to death.

Never despair! Let the feeble in spirit

Bow like the willow that stoops to the blast

Droop not in peril! ‘Tis manhood’s true merit

Nobly to struggle and hope to the last.

When by the sunshine of fortune forsaken

Faint sings the heart of the feeble with fear.

Stand like the oak of the forest – unshaken,

Never despair – Boys – Oh! Never despair.

Never despair! Though adversity rages,

Fiercely and fell as the surge on the shore,

Form as the rock of the ocean for ages.

Stem the rude torrent till danger is o’er.

Fate with its whirlwind our joy may all sever,

True to ourselves we have nothing to fear;

Be this our hope and our anchor for ever,

Never despair! – Boys – Oh! Never despair.

<———————————————————————>

Young Ireland Pageant participants, The Commons Sat July 27th 2013

William Smith O’Brien – Liam Noonan

John Blake Dillon – Bill Martin

L to R:- Back.

Terence Bellew McManus, – Mick Kavanagh

James Stephens, – Paddy Moloney

(Annie Heaphy, wardrobe)

Michael Doheny, – Dan Doheny

James Stephens – John O’ Connell

John O’ Mahony – Leslie Smyth

David Power Conyngham – Adrian Kelly

Richard O’Gorman – Matty Alexander

Smith O’Brien, James Stephens and Terence Bellow McManus remain in the Commons.

Meagher, O’Donoghue, Leyne and Thomas Devin Reilly – headed for the Comeraghs and stay with John O’Mahony at Hanrahans near Nine-Mile-House on the Friday night 28th, A messenger dispatched to Ballingarry returned with false information. The truth only became clear when they were joined by McManus who had escaped from Ballingarry. August 4thSmith O’Brien was arrested as he was waiting for a train at Thurles Station. Meagher, O’Donoghue, Leyne, Thomas Devin Reilly & John O’Mahony were all arrested near Clonoulty Sunday 13th August.

Michael Doheny went to raise Slievenamon, John Blake Dillon to raise Ballaghadereen. both escaped with James Stephens to France Oct 4th and thence to America.

SMITH O’BRIEN’S LETTER TO THE MINING COMPANY OF IRELAND

The events of the week 24 – 29 July, 1848 have special significance for the people of the Commons. The monument recently erected at the cross-roads in the village tells us that it was here in Sullivans Public House that some of Ireland’s most distinguished patriots met on the evening of Thursday 28th July, 1848 to determine a course of action for the Irish Confederation – We now know that apart from William Smith O’Brien, James Stephens, Terence Bellew McManus and Patrick O’Donohue, the other leaders left the Commons to prepare for a Rising in Autumn. The encounter at the Warhouse next day terminated all these plans. I include two items concerning 1848 in this piece, one is the little known Smith O’Brien letter to the Mining Company of Ireland which indicates his sympathy with the plight of the miners many of whom had been laid off due to the recession caused by the Famine. This letter was written some time during the early morning of 29th July, and delivered to Mr. Cullen, Manager of the collieries. It was one of the Acts of Treason with which O’Brien was later charged at Clonmel. The letter demonstrates that O’Brien was not oblivious of the world of commerce and it may well have been the first reference to nationalisation of the Mines.(Ref,William Nolan)

.

This letter is dated, 29th of July, 1848. “Mr. William Smith O’Brien presents his compliments to the Directors of the Mining Company, and feeling it incumbent upon him to do all in his power to prevent the inhabitants of the collieries from suffering inconvenience, in consequence of the noble and courageous protection afforded by them to him, takes the liberty of offering the following suggestions:- He recommends that for the present the whole of the proceeds arising weekly from the sale of coal and culm be applied in payment of men employed by contract in raising coal and culm.” “He recommends that a brisk demand be encouraged by lowering the price of coal and culm to the public.” “In case he should find that the Mining Company endeavours to distress the people by witholding wages and other means, Mr. O’Brien will instruct the colliers to occupy and work the mines on their own account; and in case the Irish revolution should succeed, the property of the Mining Company will be confiscated as national property.” “On the contrary, if the Mining Company observes a strict and honourable neutrality, doing their utmost to give support to the population of this district during their present time of difficulty and trial, then their property shall be protected to the utmost extent of Mr. O’Briens power.”

Ballingarry Murals on Young Ireland Famine Rising 1848 By Dr Thomas Mc Grath

In the village of Ballingarry the new historical murals enjoy an unbeatable location on the end wall and on the front wall of Tobin’s shop, thanks to the goodwill of Michael Tobin (RIP) and Anne Tobin. The bigger of the two murals faces out from Ballingarry looking directly towards Slievenamon and cannot be missed once one turns the corner at the cross-roads.The mural project was driven by the Ballingarry 1848 Committee comprising Martin Maher (Chairman), Marie Barry (Secretary), Jimmy Meagher, John Webster, Anthony Ivors Jnr, and Thomas Mc Grath.

Recently re-elected Councillor, Imelda Goldsborough, secured funding for the project from Tipperary County Council and the parish community provided strong support.The murals were skilfully painted by artist Neil O’Dwyer in June 2024 to a plan by the present writer. The murals commemorate the Young Ireland Famine Rising of 1848 which took place in Ballingarry and The Commons. The Young Irelanders were a brilliant group of nationalists who were goaded into a Rising by the British government’s disastrous handling of the Famine. They believed in national self-determination and that an Irish government would provide food for the people during the Famine. They were also influenced by the great initial success of the 1848 Revolutions across the European continent.There are eleven named individuals framed in oval portraits on the mural. Each of these was present in Ballingarry and The Commons during the Rising. The mural looks down on steps from where William Smith O’Brien and John Blake Dillon made speeches in 1848. Those portrayed are important figures, famous names, in the struggle for Irish freedom. They were patriots who were prepared to sacrifice everything for the cause. Between them they encapsulate much of the history of Ireland in the mid and later nineteenth century.At the top is William Smith O’Brien, the Young Ireland leader who was born in Dromoland Castle in Co Clare into the family of the ancient High Kings of Ireland, the O’Briens of Thomond. He was MP for County

Limerick in 1848 and a most severe critic of the government’s famine policy in the House of Commons in London. Though not all his followers would have agreed he sought to stage a bloodless revolution which failed once it was met by force at Famine Warhouse 1848. For his part in the Rising, O’Brien, and Thomas Francis Meagher(from Waterford), Patrick O’Donohoe (from Carlow) and Terence Bellew,Mac Manus (from Fermanagh) were tried for High Treason in Clonmel and sentenced to death. The sentences were commuted to penal transportation to Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania) from where all except O’Brien escaped to the United States of America. In Van Diemen’s Land, O’Brien wrote: ‘Often have I regretted that I was not shot at Ballingarry or executed at Clonmel’. There, when he saw the published Irish census for the decade, 1841-1851 he estimated that there had been a loss of two million people, of whom he believed, one million had

emigrated. He stated: ‘There remains one million for whose premature extinction the British government is to be held responsible’ and he added: ‘when I ponder upon the statistical return of the Irish population which lies before me I feel I did my duty when I endeavoured at the risk of my life to avert the evils which have been inflicted upon my country during the most calamitous reign that Ireland has experienced since it became subject to the British crown’. After the Rising, John Blake Dillon (from Mayo) one of the founders with Thomas Davis and Charles Gavan Duffy, of The Nation, the Young Ireland newspaper, escaped to the United States. He later became M.P. for Co. Tipperary and was the father of John Dillon, also an MP for Co.Tipperary and the last leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party in 1918, and grandfather of James Dillon who as Minister for Agriculture participated in Ballingarry in the centenary celebrations in 1948. He was subsequently

leader of Fine Gael.The tricolour has pride of place at the very top of the mural. Thomas Francis Meagher brought it home from Paris in 1848 and it is commemorated at the National Flag Monument in the village of The Commons where it is raised daily by John Webster and was previously raised by the late Anthony Ivors. Meagher made a speech in The Commons in 1848.The European Union flag on the mural references the fact that the leading countries in Europe were affected by the Revolutions of 1848.Revolution swept across the continent from Paris to Berlin, Rome, Vienna,Prague, Budapest, and Bucharest, and a great number of cities in-between.The continental revolutions broke out in the cause of democratic freedoms,liberalism, and national self determination. All of the above capital cities are in countries, along with Ireland, now in the European Union which endeavours to uphold democratic ideas similar to those of 1848.

The USA flag on the mural stands for the Irish who fled from the Famine, the vast majority of whom went into exile in the United States (including the McCormack family in 1851). It also acknowledges the fact that eight of the eleven Young Irelanders on the mural died in the United States. Five of them held military rank during the US Civil War: one Brigadier General, two Colonels, one Major and one Captain. Brigadier General Thomas Francis Meagher died as acting governor of Montana. David Power Cunningham (who used the alias Conyngham for his

books) was from Crohane near Ballingarry. Under O’Brien’s command he drilled men on Ballingarry Fair Green during the Rising. In the US he was staff officer to Thomas Francis Meagher in the Union Army and later attained the rank of Major. He was a newspaper editor, novelist, and historian. Author of many works, his book The Irish Brigade and its campaigns is a famous source for the Irish in the US Civil War. He put up the headstone to his Cunningham family members which can be seen in Lismalin graveyard. He died in New York and is buried there. John Kavanagh from Dublin was seriously wounded at the Famine Warhouse. His eyewitness account of being under fire there is in the exhibition in the house museum. He died at the age of thirty-four in 1862 as

a Captain fighting under Meagher at the great US Civil War battle of Antietam.Terence Bellew Mac Manus who was also wounded in Ballingarry died in California in 1861. His funeral, after exhumation in San Francisco, to Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin is one of the most famous funerals in Irish history. His eyewitness account of the exchange of fire during the Rising is also given in the exhibition in the museum. On the lower line of portraits is Thomas Devin Reilly from Co Monaghan, journalist on The Nation and The United Irishman newspapers and a close ally of John Mitchel. He died in New York where he worked as a newspaper editor at the early age of twenty-nine. The barrister Michael Doheny was born near Fethard (into a family with links to Shangarry) and lived in Cashel. Less than two weeks before the Rising, Doheny and Meagher addressed a great meeting of thousands of Young Ireland supporters on top of Slievenamon; Doheny said ‘this shall be the last year of famine and misrule in this country…. The time is fast approaching when Ireland shall again be free. I have said before that the time for speech making is past, and the time for action come. Let us swear to God that this year will not go by till Ireland is a free nation’. Doheny’s book The Felon’s Track is a celebrated account of his escape after Ballingarry with James Stephens through the mountains of Munster. John O’Mahony was from Mullagh near Carrick-on-Suir. Around Carrick he tried to revive the Rising after Ballingarry with attacks on police

stations. He escaped first to France and then to America. A Gaelic scholar hedied in the USA in 1877 and was buried in Glasnevin. His relation Charles Kickham from Mullinahone gave the oration at his funeral. Doheny and O’Mahony held the rank of Colonel in the US. James Stephens from Kilkenny was also under fire in Ballingarry in 1848. A death notice for him was published to put the police, who were searching for him, off the scent. Doheny, O’Mahony and Stephens founded the Fenian movement or I.R.B which was responsible for the Risings of 1867 and 1916. From the 1916 Rising we trace our freedom. Thus there is a direct link between 1848 and 1916. The 1848 Rising took place in the middle of the Great Famine – a fact which determined its timing and its course – but one that is often overlooked as if 1848 can be divorced from its context. A million people were dying in Ireland at this time as another million were fleeing the country. The interpretation of a Famine Rising put forward by the present writer in the official name change of the scene of the Rising to Famine Warhouse 1848 (in 2004), in the exhibition in the house museum, and in the annual Famine 1848 Walk (since 2006) on the day of the Rising, offers a new Irish narrative in place of the racist and anti-Irish origins of the British press narrative which has often been unthinkingly accepted in the past. The State National Famine Commemoration was held at Famine Warhouse 1848 in 2017. To one side of the mural is the graveyard in Ballingarry where a great number of local famine victims were buried. As the Ballingarry priest, Fr Fitzgerald, wrote during the Famine: there was no grass to be seen in the parish graveyards because they had been completely dug up for burials.The new murals, along with the mining mural on Ryans Miners’ Rest, are proving to be visitor attractions in their own right in Ballingarry and have already been much photographed. The reference to ‘South Tipperary’ on the bigger mural, a suggestion of Councillor Imelda Goldsborough, is to distinguish the location from Ballingarry in North Tipperary, Ballingarry in Co. Limerick, and other Ballingarrys elsewhere. The original recommendation that the big wall of Tobin’s shop would be a suitable location for a mural was made by Michael Mc Grath in the Ballingarry Tidy Towns committee. The smaller mural on the front of Tobin’s shop gives images, signposts directions and details of distances to the related historic sites to

visit: the National Flag monument in The Commons Village, and Famine Warhouse 1848, the national heritage museum where John Webster is the caretaker. There is also a QR code giving plenty of information. In 1848 in the middle of the catastrophic famine and the most terrible period in Irish history it was important for national self-respect that the Irish people or at least the Young Irelanders and the people of Ballingarry and The Commons were prepared to make a stand for freedom. It is not surprising that this is a source of pride to the parish community. The new

murals draw attention to the fact that Ballingarry is an important location in Irish national history with strong European and transatlantic dimensions.

The above article was published in the Ballingarry Parish Journal 2024 in November 2024.

The small mural in the centre of Ballingarry village at Tobin’s shop with directions to related historic sites to visit: the National Flag Monument in The Commons’ village and the State national heritage site and museum: Famine Warhouse 1848.